Apocalypse at Solentiname - Julio recounts his trip to Solentiname, an island archipelago in Lake Nicaragua, just north of Costa Rica.

Julio

and a few of his writer friends, Carmen Naranjo, Samuel Rovinski,

Sergio Ramirez, fly in an Piper Aztec with a blonde pilot, the plane

letting loose a few hiccoughs and bowel rumblings as the pilot hummed

calypso songs while seemingly not hearing Julio tell him the Aztec was

taking everyone straight to the sacrificial pyramid.

Oh, wow, echoes of Julio's short-story The Night Face Up

where a young man is taken to a hospital following a motorcycle

accident and there's a crossover between dream and reality, between a

procedure on an operating table in a modern hospital and a blood

sacrifice on the alter of an Aztec temple. And as Julio learns when he's

back in his Paris apartment, his statement serves as a foreshadow of

what's to come.

Once Julio is on Solentiname and everyone else

has gone to bed, he discovers a number of paintings done by local

peasants stacked up in the corner of the community hall: midget cows in

poppy fields, people emerging from a sugar-making shed, a horse with green

eyes, a baptism in a church, a lake with little boats, a mother with two

children on her knees. All so clean, so incredibly beautiful.

Julio

relates what happened next: "The next day was Sunday and eleven o'clock

mass, the Solentiname mass in which the peasants and Ernesto and the

visiting friends comment together on a chapter of Scripture which that

day was Jesus' arrest in the garden, a theme that the people of

Solentiname treated as if they were talking about themselves, about the

threat of being pounced on at night or in broad daylight, that life of

permanent uncertainty on the islands and on the mainland and in all of

Nicaragua and, yes, almost all of Latin America, a life surrounded by

fear and death, life in Guatemala and life in El Salvador, life in

Argentina and Bolivia, life in Chile and Santo Domingo, life in

Paraguay, life in Brazil and Colombia."

Following mass, Julio is

drawn to the paintings. "I went to the community hall and began to look

at them in the dazzling light of noon, the bright colors, the acrylics

or oils facing each other out of their ponies and sunflowers and fiestas

in the symmetrical fields and palm groves." Julio remembers he has a

roll of color film in his camera and goes out onto the porch with an

armful of paintings. Julio then begins photographing the peasants'

artwork carefully, one by one, centering each painting so that they fill

the viewer completely. So happens Julio has just enough film to snap a

photo of each and every one. When Julio tells Ernesto what he's done,

Ernesto laughs and calls Julio an art thief, an image smuggler.

On

his return to Paris following two months of visits to counties in Latin

America, Julio's friend Claudine takes his rolls of film to be

developed.

One evening thereafter, Julio decides to take a look

at the photos, the photos of Solentiname first. But then the shock.

Julio can hardly believe what he sees: a boy with a neat hole in the

middle of his forehead, an officer's pistol and other officers off to

the side with their submachine guns, people gathered to the left looking

at bodies laid out face up. No! There must have been some mistake and

mix up. But Julio continues looking - more violence: four guys in a

black car in Buenos Aires taking aim at someone on the sidewalk, two

women trying to take cover behind a parked truck, a naked girl on her

back and shadow of shoulders putting a wire between her open legs. More

photos; more violence and brutality.

Claudine returns. Claudine

bends over and kisses Julio on the hair and asks him if the photos came

out well and if he was pleased with the pictures, if he feels like

showing them. Julio clicks the carrousel and puts it back to zero.

Julio, his body one single knot, leaves the room, goes to the bathroom

and throws up. When he returns, Claudine tells him the photos came out

well - the photos she seen are the beautiful ones Julio recalls taking.

During one of his classes at a university in the United States, Julio Cortázar read Apocalypse at Solentiname

and remarked: "I think that in a story of this kind the sudden

appearance of an entirely uncanny element - entirely and decisively

fantastic - makes reality more real and brings the reader something

that, if stated explicitly or recounted in detail, would have ended up

being one more report about all the many things that are going on, but

within the story it is shown strongly enough, through the mechanism of

the story itself."

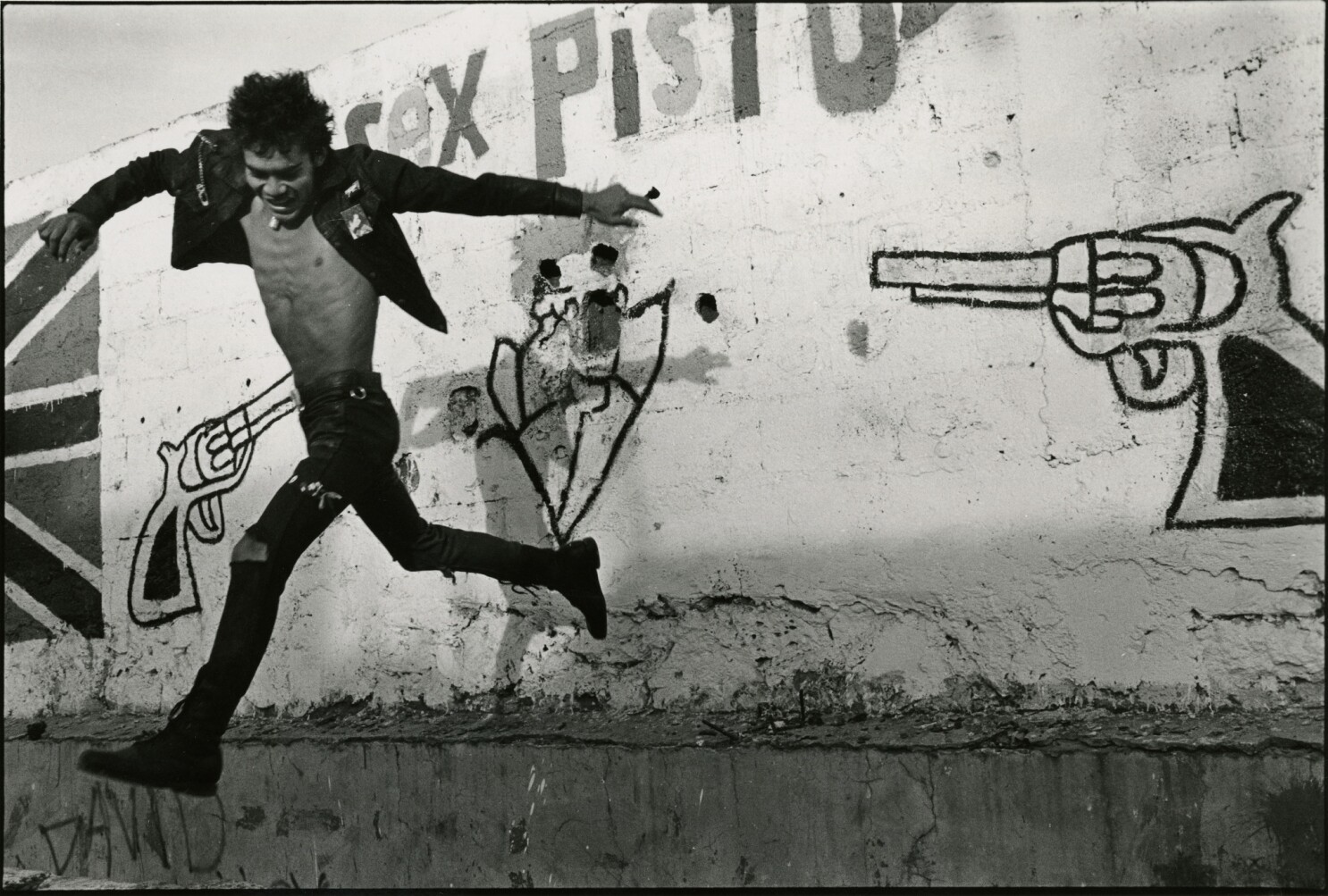

For many readers, including myself, Apocalypse at Solentiname brings to mind the photographer in Blow Up

who discovers, via a careful examination of his photos, a violence

lurking in the shadows. Recall Walter Benjamin writing in his Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction:

"technical reproduction can put the copy of the original into

situations which would be out of reach for the original itself."

I

highly recommend a careful reading of this Julio Cortázar tale. Perhaps

you will make a number of your own discoveries I have only hinted at in

my brief review.

Comments

Post a Comment