A PERMANENT HOME (Una casa para siempre) is a sizzling Enrique Vila-Matas short story that's included in Vampire in Love and other stories,

translated into eminently readable English by Margaret Jull Costa.

Spoiler Alert: In order to do a measure of literary justice here, I'm

obliged to cover this phenomenal tale from beginning to end, a tale

packing so much into a mere seven pages.

The unnamed narrator

reveals that he never knew much about his mother since she was killed in

their house in Barcelona just two days after his birth. Then, when the

narrator, a gentleman I'll refer to as Luis, reaches the age of twenty,

his father summons him to his deathbed to reveal something of critical

importance: he himself, his father, arranged the death of his mother.

Luis

always imagined a hired killer but, once he recovers from the initial

shock, begins to believe his father's confession, a man “devoting

himself with implacable regularity and monstrous perseverance to the

solitary ritual of creating his own language through the writing of a

book of memories or an inventory of nostalgias, which I always assumed

would, when he died, become part of my tender, albeit terrifying,

inheritance.” I've included this extended quote to underscores Enrique

Vila-Matas's focus on language, writing, and memoir, subjects running as

a common thread throughout his fiction.

Luis's father married

his mother because, by his calculation, she was perfect: extraordinarily

naive and docile, a poor orphan who would especially appreciate the

security, comfort, and wealth he could offer her. Quite different from

his two previous wives: hell-raisers who would fly into fits of rage at

the slighted provocation and sometimes even physically attack him, as

was the case with his first wife who bit off half his ear.

Upon

receiving his father's imploring letter, his mother turned up in

Barcelona where she knocked on the door of his mansion. When his mother

entered the house, his father tells Luis he was overcome with the most

intensely erotic impulse he had ever felt. And when she told him she was

an expert at dancing the tirana, a long-forgotten medieval

Spanish dance, he ordered her to dance, which she did until collapsing,

exhausted, in his arms. Whereupon he affectionately ordered her to marry

him at once. And that night when they slept together, his father said

he experienced undreamed of bliss. And it was that very night when he

was conceived. Sidebar: a telling detail of his father's view of men and

women - he didn't ask his mother to marry him; rather, he ordered her

to do so.

What transpires next in this Enrique Vila-Matas tale is

quite remarkable. Luis's dying father requests a glass of vodka. After

an initial hesitation, Luis goes down to the kitchen and fills two

glasses. Luis can see his Aunt Consuelo entirely absorbed by her desire

for a particularly painting hanging in the living room, a painting of

angles climbing a ladder. And then the shocker: Luis says his Aunt's

absorption is similar to his father's. “And he, at that moment, was

entirely absorbed in feeding the illusion of his story.” Ah, so we could

very well be listening to a dying man's fabrication. This fact is

reinforced when his father explains what happened on their honeymoon,

confusing Paris and London with Istanbul and Cairo.

His father

goes on to note his wife's odd obsession: she collected bread rolls.

Visiting Istanbul bakeries became a kind of strange sport. When he

protested and asked why bread rolls, she replied as if humoring a

madman, “The troops have to eat something.” The strangeness continues.

At night, his wife began talking in her sleep, barking out implacable

commands: “Fall in!” “Right turn!” “Break ranks!” Reveille, he father

tells him, “became a real torment, because every day, minutes before

your mother woke, her snoring appeared to be imitating the unmistakable

sound of a bugle at dawn.” Luis is taken aback, wondering if, while on

the verge of dying, his father's sense of humor along with his flair for

storytelling is magnificently on display here.

A Permanent House

contains much colorful detail, including how his mother began to take

on the role of army general constantly shooting out orders to his poor

father. I've only touched on several highlights in my compressed

retelling. You'll have to read for yourself. I'll end with quoting the

concluding paragraph that curiously mirrors the words at the end of

Enrique Vila-Matas' novel, Mac's Problem:

“My father, who

had once believed in many, many things only to end up distrusting all

of them, was leaving me with a unique definitive faith: that of

believing in a fiction that one knows to be fiction, aware that this is

all that exists, and that the exquisite truth consists in knowing that

it is a fiction and that, nevertheless, one should believe in it.”

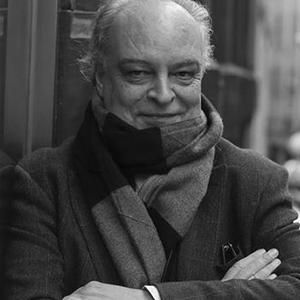

Spanish author Enrique Vila-Matas, born 1948

Comments

Post a Comment