Following one particularly ghastly episode involving the hacking up of a stolen corpse from a church graveyard, the Divinity Student places a call from a public telephone to the occult leader orchestrating these macabre events, reporting unexpected difficulties with his latest assignment. The leader, a necromancer by the name of Fasvergil, barks back: “Itemize the damages. I’ll expect a report on this.”

This is velvet vintage Michael Cisco: not only are we given grisly, ghoulish Gothic horror (in this chapter, the Divinity Student must swallow the corpse’s liver), but Cisco peppers in the white-collar banality of filing expenses. What?! Since when does a sorcerer, wizard, or satanist need to itemize damages to complete an expense report? This shocking combination is what makes The Divinity Student so singular and unsettling.

Along with writers such as China Miéville, Jeff VanderMeer, Mark Z. Danielewski, Kelly Link, and Thomas Ligotti, Michael Cisco’s writing is frequently classified as “New Weird.” To emphasize just how weird literary fiction labeled “New Weird” can be, here are a number of examples from the first two chapters:

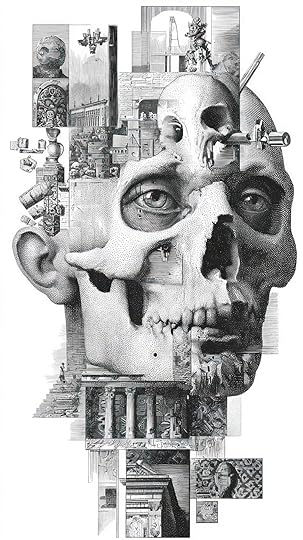

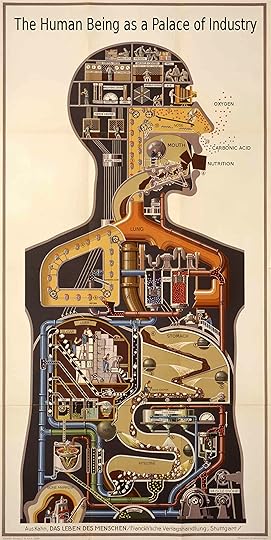

The Divinity Student enjoys a hike, but then it happens: he falls down dead and is taken to a low building where he is cut open from throat to waist, his innards ripped out, and he's stuffed with pages from many different random texts. His return to life as a textual being underscores the way literature can figuratively transform an individual, rewiring perceptions and cognition. Recall that Michael Cisco is a Deleuzian, and the cover art for Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus is Man as the Palace of Industry by Fritz Kahn. We can envision this artwork with written texts in place of all the mechanized gizmos and gadgets. The Student’s body has been repurposed, changed into a vehicle “to set him to the task.” Ominous, ominous—there’s little doubt we’ve crossed into a world of surreal horror.

The Student, in the infirmary following his ordeal, feels there is something mechanical about his hands, which fits neatly into a Deleuzian register: his hands are no longer exclusively his own; rather, they are components within a wider process. What process? The head of the seminary, a grim, menacing figure named Fasvergil, provides a sinister glimpse: he sends the Student off to the city on a yet-to-be-disclosed assignment. The Student offers no objection; he simply replies that he’ll do what he’s told, which signals a diabolical shift: he is less an autonomous individual than a desiring-machine calibrated to accord with institutional flows—precisely the process Deleuze and Guattari delineate.

As the Student travels across a desert via taxi to the city of San Venefico, he spots “the famous monitors, giant lizards over ten feet long, racing with alarming speed.” These immense lizards alert us that we are far removed from any trace of realism. In Cisco’s clear, matter-of-fact, clinical prose, the fantastic is simply a given element of land and city—a city named San Venefico (veneficium = sorcery, poison), a place that seems to sanctify danger and the occult.

Once in San Venefico, the Student sits on the clammy bank of a colossal fountain in the middle of a main plaza, with buildings for giants looming all around, knowing he has a letter directing him to obtain a position with a professional word-finder and await further instruction. “Unthinkingly, he reaches into another pocket and produces a small metal weight on a cord that Fasvergil had given him back at the Seminary. Sheltering himself from crowd and wind, he spits in his palm and swings the weight like a pendulum above his open hand.” The Student’s absorption in the metal weight has an eerie resemblance to a painting Deleuze and Guattari reference to undergird their philosophy of how people become part of desiring-machines, trapped in flows of energy and production: Boy with Machine by Richard Lindner. And the fact that Fasvergil gave him this object indicates it isn’t for innocent play but a tool to bind the Student to authority.

The Student wends his steps to the office where he’ll be working as the new word-finder. In the way Cisco describes the office itself and the office workers, we have the distinct impression the Student has walked into a nightmare—cold, mechanical, and icily depersonalized. He takes his place at a desk in an odd-shaped room with three other clerks and is immediately on the receiving end of hostility, especially from one clerk who looks like a grown-up version of Lindner’s Boy with Machine. Again, we think of Deleuze and Guattari: a world drained of even a trace of warmth, human bodies and human relations reduced to machine processes.

As indicated above, what I’ve detailed is taken from just the first two chapters. Cisco’s novel runs to eighteen chapters, each one shifting, sliding, and building on the surreal, absurd, grotesque, revolting, and horrific. Added to this, the pages are laced with dream logic from the art of Salvador Dalí and the prose of Guillaume Apollinaire, hallucinations that call to mind Sadegh Hedayat’s The Blind Owl, the breathtaking visions in Hermann Hesse’s Magic Theater, and violence — abundant violence — as the fictional counterpart to the paintings of Francis Bacon. How will it all end after the Student takes up residence in a meat freezer, experiences extreme paranoia, encounters wizards, and even an acrobatic muse? That is for Michael Cisco to tell.

Michael Cisco is now on my list of favorite authors. I plan to read and review The Golem, The Tyrant, The Traitor, Secret Hours (a collection of his short stories), and his mammoth masterpiece, Animal Money. The Divinity Student will open your imagination in the uncanniest ways. Your mind may never be the same again.

American author and Deleuzian academic Michael Cisco, born 1970

Sometimes I swear that we are reading from the same shelf. This is a book that goes under many peoples' radars.

ReplyDeleteMichael Cisco is new to me. I plan to read and post reviews for his other work, starting with The Golem, The Tyrant, The Traitor, Secret Hours, and Animal Money.

ReplyDelete