The Hoegbotton Guide to the Early History of the City of Ambergris by Duncan Shriek by Jeff VanderMeer

If there is any tale in the Ambergris cycle where Jeff VanderMeer most deserves comparison to Borges and Calvino, it is The Hoegbotton Guide to the Early History of the City of Ambergris by Duncan Shriek, first published in 1999 by Necropolitan Press and later included in City of Saints and Madmen. I say this after multiple rereads. Historian Duncan Shriek’s prime source material for compiling the history we are reading is the secret journal of the Truffidian monk Samuel Tonsure.

But eventually we learn there are rumors the journal is a forgery. So how are we to know what should be taken as actual historical fact? Shriek assures us he tried his best in laying out the eighty-five pages and 137 footnotes (137!) that comprise his account, ending with a final footnote: “Surely, after all, it is more comforting to believe that the sources on which this account is based are truthful, that this has not all, in fact, been one huge, monstrous lie?” Come, come, Duncan— “more comforting to believe” hardly counts as solid, reliable history. Once again VanderMeer refuses to be pinned down. If there is one word to characterize what is written here, it is destabilize. That’s right—enjoy your reading, but keep in mind that when it comes to the historical record of Ambergris, the footing is always a tad slippery.

To share a taste of the Hoegbotton Guide, here are several distinctive bits of city history, each coupled with my own reflections.

John Manzikert – A whaler turned pirate, this Cappan (their word for captain) sails with his wife, Sophia, and with Tonsure aboard (a great name—I wonder if the top of his head was shaven). Manzikert led his fleet of 30 whaling ships up the River Moth to escape a rival who had decimated his once-proud fleet of 100. This has a familiar ring from our own world: war as the reason and prime mover for change. In this case, it was the first human incursion into the territory that would eventually become Ambergris.

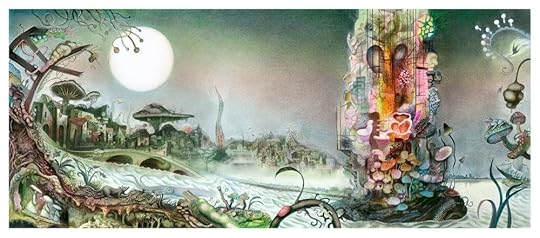

Strange Inhabitants – Surely the most distinctive feature of VanderMeer’s cycle of three novels beginning with City of Saints and Madmen are the so-called gray caps, or mushroom dwellers, who populate the city. They are beings the size of a six-year-old child, grayish in color, with distinctive caps that resemble the tops of mushrooms. When Manzikert attempted a conversation with the unattractive gray caps, they “could not answer except in a series of clicks, grunts, and whistles.” The reaction of Manzikert, Tonsure, and the rest? To dismiss the gray caps as inferior and subhuman—reason and justification for wholesale slaughter and the seizing of their land and property. Again, we recognized the brutality of our own world: the destruction of peoples and civilizations, from the Aztecs and Incas to the tribes of the Amazon rainforest.

Life Overflowing – Such a rich land, with “the abundance of tame rats as large as cats, the plethora of exotic birds, and, of course, the large quantities of fungus, which the gray caps appeared to harvest, eat, and store against future famine.” As for the buildings—“Its architects had built circles within circles, domes within domes, and circles within domes.” Additionally: “Just as delightful were the huge, festive mosaics lining the walls, most of which depicted battles or mushroom harvesting, while a few consisted of abstract shiftings of red and black.” We also discover how Manzikert developed (gulp!) a special relationship with those supersized rats. The more we read, the more we appreciate how VanderMeer’s breathtaking creation lets our imagination run weird-ass wild.

Literature and the Fine Arts – In one of Duncan Shriek’s many footnotes, we learn of the adventures and misadventures of novelist George Leopran. This is eye-opening—in the early history of Ambergris, the writing of novels is already an accepted literary form. That suggests a modern sensibility akin to Europe since the time of Cervantes. Quite the combination for a city otherwise depicted as possessing many qualities of a medieval urban center. VanderMeer reinforces the sense that Ambergris belongs entirely to his own imagination. Personally, I would love to read a novel—or two or three—written during the early history of Ambergris.

Dramatic Turn – Following the festival that Manzikert and Sophia hold to celebrate the founding of what the Cappan christens his new settlement—Ambergris—tragedy strikes. Manzikert beholds a sacrilegious image he believes created by the gray caps and flies into a rage. He gathers a force of 200 men and orders them to slaughter the gray caps. This proves a “horribly mute affair,” since the gray caps offer no resistance. “The bodies were so numerous that they had to be stacked in piles so that Manzikert and his men could navigate the streets back to the docks.” But then a gray cap, dressed in purple robes by his altar, makes an “unmistakably rude gesture” at Manzikert and flees up the stairs of the city’s great library. Manzikert pursues with a select group of men, including Tonsure.

However, the night passes and Manzikert does not return. Then the shock: the next morning Sophia leads a force of 300 men into the city, only to find not a trace of blood. It is as if the massacre never happened. What she does discover in the library is a weeping Manzikert, covering his face with his hands. When Sophia pries them away, she sees that his eyes have been plucked out. Enraged, Sophia orders the burning of the city and, when all is reduced to ashes, the sealing off of the underground, gray cap–infested sections. Reading this sad episode, are we surprised at the consequences when leaders are motivated by rage? No doubt this marks a sharp twist in the city’s history.

The Silence – “Any historian must take extreme care when discussing the Silence, for the enormity of the event demands respect.” So writes Duncan Shriek. He acknowledges a common soldier by the name of Simon Jersak, who left a full account of an army’s expedition into Ambergris—an Ambergris completely devoid of men, women, and children. The army reported back that they found “meals lay on tables ready to eat, and carts with horses stood placidly by the sides of the avenues that, even at the early hour, would normally have been abustle. But nowhere could they find a soul: the banks were unlocked and empty, while in the Religious Quarter, the flags still weakly fluttered, and the giant rats meandered about the countryside, but again, no people.”

What they did find on the altar of the giant church was “an old weathered journal and two human eyeballs preserved by some unknown process in a solid square made of an unknown clear metal… The journal was, of course, the one that had disappeared with Samuel Tonsure 60 years before. The eyes, a fierce blue, could belong to no one but Manzikert I.” Everyone in the army, including their leader Aquelus, recognized this as the unmistakable return of the gray caps.

I've only touched on several of the many colorful events and details in this early history. For a full account, I highly recommend a careful read of VanderMeer's novella. I'm confident you'll be inspired to then dive into City of Saints and Madmen.

American author Jeff VanderMeer, born 1968

Comments

Post a Comment