"Peter Hunkeler, inspector with the Basel City criminal investigation department, formerly married with a daughter, now divorced, was asleep in his house in Alsace." So begins Hansjörg Schneider's The Murder of Anton Livius, an absorbing work of crime fiction written in fifty-five short, unnumbered chapters.

I found the Swiss author’s 220-page novel gripping from the very first chapter, as if I were living Hunkeler’s experience scene by scene—feeling the winter cold, watching as snow continually covers the frozen ground, listening intently to each spoken word in the inspector’s many encounters. Moreover, I had the sense that Hansjörg Schneider was responding to a call issued by generations of denizens along the Swiss French border, both in the countryside and in and around Basel. To be more specific, I will now shift to a list of highlights.

MURDER — Early on New Year’s morning, Hunkeler receives a call from the station: Anton Flückiger, also known as Anton Livius, born in 1922, a man in his eighties who came to Switzerland after World War II and was later granted citizenship, has been found shot in the forehead and hung from a meat hook rammed under his chin, his body discovered in the cabin on his allotment on the French side of the border.

SWISS AND FRENCH POLICE — A Swiss citizen murdered on French soil means Basel detectives must assist the Police nationale based in Alsace, with both countries required to work together to solve the crime. Herein lies much of the novel’s drama: during the police briefings, the uptight Swiss and arrogant French repeatedly point fingers at one another, pound the table, and boil over with rage. Meanwhile, Hunkeler—a lone wolf by nature, with a house in Alsace and a flat in Basel—knows he must slip back and forth across the border, piecing together clues from the scant information made available to him.

THE ALLOTMENTS — One of the police officers observes, “There’s some sort of culture war going on in the allotments. In that respect, they reflect our society as a whole.” Another officer chimes in: “It all started when some of the people from the Balkans and Turkey got into the habit of listening to music very loudly. And I mean their own kind of music. Belly dancing stuff or the devil knows what.” Ah yes—Switzerland today is very much a multiethnic society, a dynamic that Hansjörg Schneider does not hesitate to spotlight as both French and Swiss officials plod through the social muck surrounding the murder.

LONE WOLF COMES TO TOWN — Hunkeler knows he is not permitted to investigate on French soil, yet he drives to the village of Ballersdorf, posing as a novelist doing research. Standing in the village cemetery, he is fortunate enough to gather fragments of history reaching back to World War II, when the Germans forced young Frenchmen to fight on their behalf in Siberia, and a group of those men attempted to escape to Switzerland. One elderly local tells him, “Three of them had been shot dead at the railway embankment that night, by a German patrol. One got away. The others ran home. On Sunday morning they came to early Mass with their parents as if nothing had happened. The Gestapo fetched them out and took them to Struthof. I can remember that very clearly, how them were hauled out of mass. The whole village prayed. It didn't help.” Many threads lead back to Anton Livius, and the more Hunkeler sniffs around, the tighter those connections become.

LONE WOLF AND HIS HONEY — Peter Hunkeler may be an older man nearing retirement, but he enjoys a warm, affectionate relationship with his attractive, much younger girlfriend, Hedwig. Even so, Hansjörg Schneider keeps his focus firmly on the murder investigation. Unlike many contemporary crime novelists, Schneider does not spin out pages of domestic drama, nor does he burden the reader with a detailed backstory involving Hunkeler’s daughter or former wife. Instead, Hunkeler simply checks in with Hedwig from time to time—a narrative choice entirely in keeping with Schneider’s prose: sharp, economical, and unornamented, recalling the classic restraint of Georges Simenon and Frédéric Dard.

THE MEDIA — At one of the police briefings, all assembled realize that a Zurich tabloid is already a step ahead in gathering critical information about the Livius murder, making the authorities themselves look foolish. Chastened, both the French and Swiss agree to intensify their cooperation. In this episode, Hansjörg Schneider quietly underscores the profound influence contemporary media exerts on public perception—and on the conduct of official investigations.

THE WRITER — At a local bar, Hunkeler exchanges reflections with a novelist who is using the Anton Livius case as the basis for his next book. When the writer outlines what he imagines to be the truth behind the murder, the Basel detective tells him, in so many words, that he is completely off base. With a touch of irony, however, we eventually learn that the writer’s logic comes remarkably close to hitting the bullseye—an episode that can be read as Hansjörg Schneider quietly reminding us that storytelling can be dangerous, and occasionally accurate.

Once again, The Murder of Anton Livius makes for a gripping, deeply absorbing read. For me, the novel brings to mind Jean-Louis Chrétien’s philosophy of art as a matter of call and response. First comes the call: in this case, Hansjörg Schneider responding attentively to the world he knows—the cultural ground along the Swiss–French border north of Basel, the lingering memory of World War II in that region, the multiethnic social climate, and the moral weight borne by ordinary lives. Then comes the response: my own, as a reader, answering the author’s acute and patient listening.

Many thanks are due to Astrid Freuler for her clear, accessible translation, and to Bitter Lemon Press for publishing this novel along with three others by Schneider. I very much look forward to reading—and reviewing—more of Hansjörg Schneider’s work.

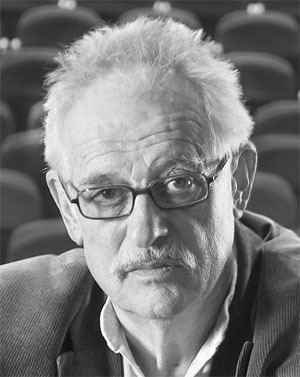

Swiss author Hansjörg Schneider, born 1938

Comments

Post a Comment